In addition to engaging your brain for eleven minutes, the goal of this piece is to:

Provide evidence for the value of copyright law

Demonstrate how modern technology complicates copyright enforcement

Suggest a path forward for creating a thriving art ecosystem in the age of AI

Part 1: How Napoleon accidentally created the perfect economics experiment

By 1796, Napoleon Bonaparte was doing what he did best: conquering. After successfully taking Northern Italy, he set off for Egypt to go look at some rocks. But while he was occupied deciphering the Rosetta stone, the Austrians and Russians seized their chance to reclaim his Italian territories. Napoleon, hearing of political instability back home (and perhaps feeling befuddled by the stone), abandoned his army in Egypt, returned to France, staged a coup d'état, and headed back to Italy for round two.

Meanwhile, another force was conquering Italy: opera. Yes, the people singing dramatically on stage, I promise this is all going to connect. Opera performances drew crowds that would rival rock concerts. A French writer reporting on a performance of Rossini’s La Scala di Seta described

. . . an immense concourse of people, assembled from every quarter of Venice, and even from the Terra Firma. . . who, during the greater part of the afternoon, had besieged the doors; who had been forced to wait whole hours in the passages, and at last to endure the ‘tug of war’ at the opening of the doors.

. . . basically the 19th century equivalent of sleeping in a tent outside a Taylor Swift concert to hold a good spot in line.

But back to Napoleon. In 1800, this short king reconquers Northern Italy and brings the Northern Italian states of Lombardy and Venetia back under French rule (and French law). But as he continues farther south, Napoleon's influence grows a bit weaker. He establishes the Kingdom of Naples and sends his brother to govern it, but it retains some autonomy from France.

Nevertheless, France is feeling pretty good. They had their revolution a few years back, overthrew the monarchy, and there's a strong "power to the people" sentiment. For example, they want to recognize authors' rights as natural rights of creators rather than royal privileges (as they were before), so they establish copyright laws enabling authors to claim royalties whenever their work is performed or reproduced.

One RESULT of all this is that only those two Northern Italian states - Lombardy and Venetia - ended up with the copyright protection while the rest of Italy (the Kingdom of Naples) remained a copyright-free zone.

So at the turn of the 19th century you have a bunch of Italian states that are basically identical in terms of culture, economy, and their love for loud singing, but some have copyright protection, and some don't.

Rarely does the universe present such a nice little controlled experiment to study public policy.

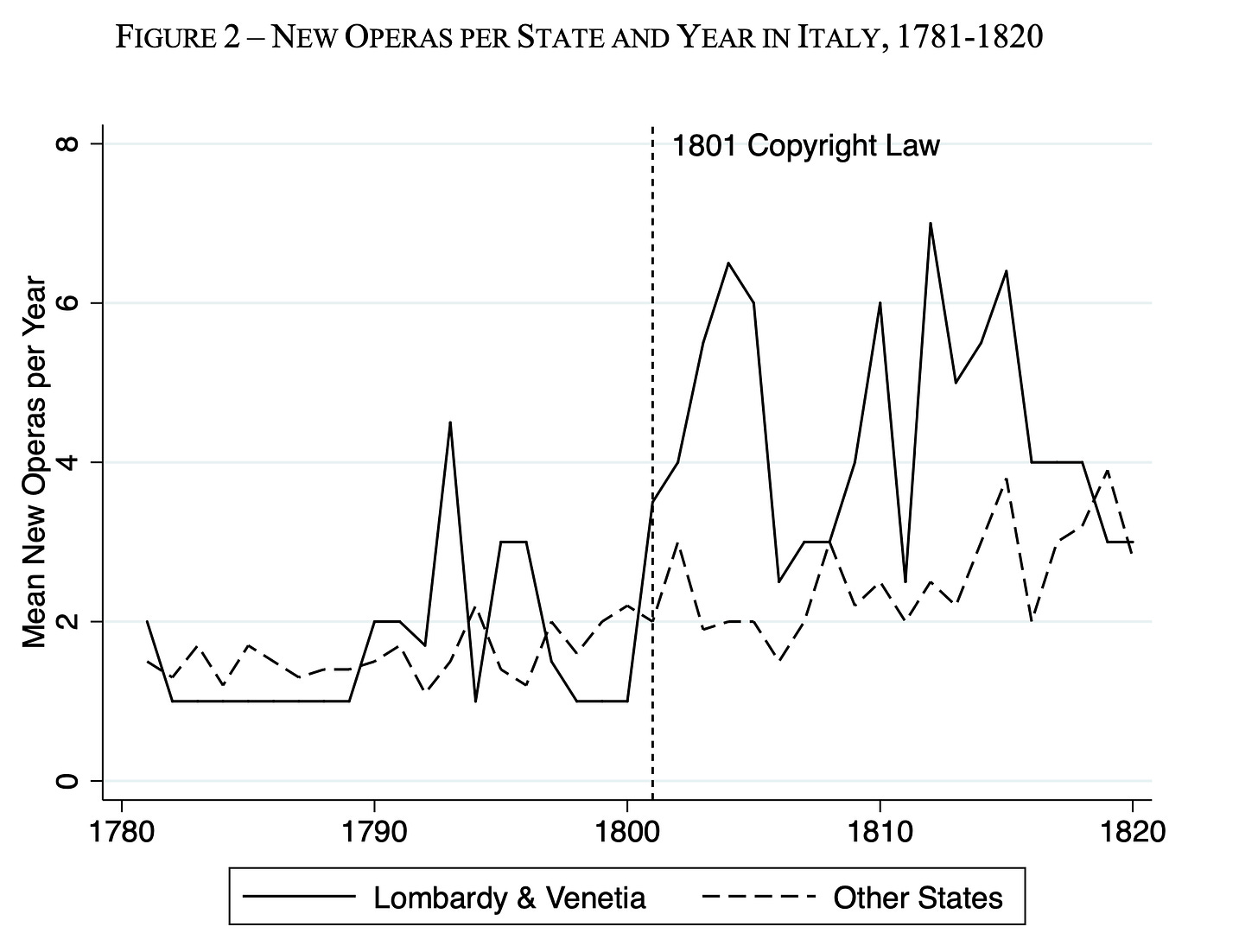

In 2020, economists Michela Giorcelli and Petra Moser seized the opportunity and wrote this epic paper comparing the quantity and quality of operas produced in different parts of Italy to study the effects of copyright protection on creative output (see, it connects!).

Between 1801 and 1826, Italian composers in those copyright-free states would be hired by a theater to compose an opera, and they would be paid a one-time fee after delivering their work. From then on, the composer had no rights to demand additional fees. In Lombardy and Venetia, however, the glorious populist French copyright laws meant that composers were entitled to compensation every time their work was performed for the rest of their life (plus an additional ten years, during which their heirs would receive the payments).

Giorcelli and Moser found that copyright protection in Lombardy and Venetia lead to a 157% increase in new opera production compared to their copyright-free neighbors. They more than doubled their creative output. Furthermore, upon counting the number of repeat performances over the following centuries, Giorcelli and Moser determined that the copyright-protected states didn't just produce more operas - they produced better operas as well.

Copyright protection helped foster the 19th-century equivalent of the modern music industry. In Lombardy and Venetia, an ecosystem of publishers, managers, and theaters flourished as investments in successful operas could be recouped over decades.

It's worth noting, however, that when Italian states later extended copyright terms to last far beyond a composer's death, it didn't significantly impact creative output. In fact, some evidence suggests these super-long copyright terms actually reduced net creative output.

My takeaways from Napoleon’s accidental experiment are:

Basic creator rights matter. When creators can profit from reproductions of their work, they make more stuff and better stuff.

But infinite protection isn't necessary. We don't need copyright terms that last until the heat death of the universe. Protection during a creator's lifetime is enough to encourage peak creativity.

It's about ecosystems, not just individuals. Copyright protection isn't just about lone creators - it's about enabling entire creative industries to develop and thrive.

Part 2: Copyright and art today

While composers in Napoleon's Italy worried about unauthorized opera performances in neighboring theaters, today's creators face a world where their work can be instantly copied, transformed, and shared by anyone with an internet connection. No longer constrained by one's ability to smuggle rolls of sheet music from Venice and Milan, infringing on copyright is easier than ever, but the methods of copyright enforcement have changed remarkably little.

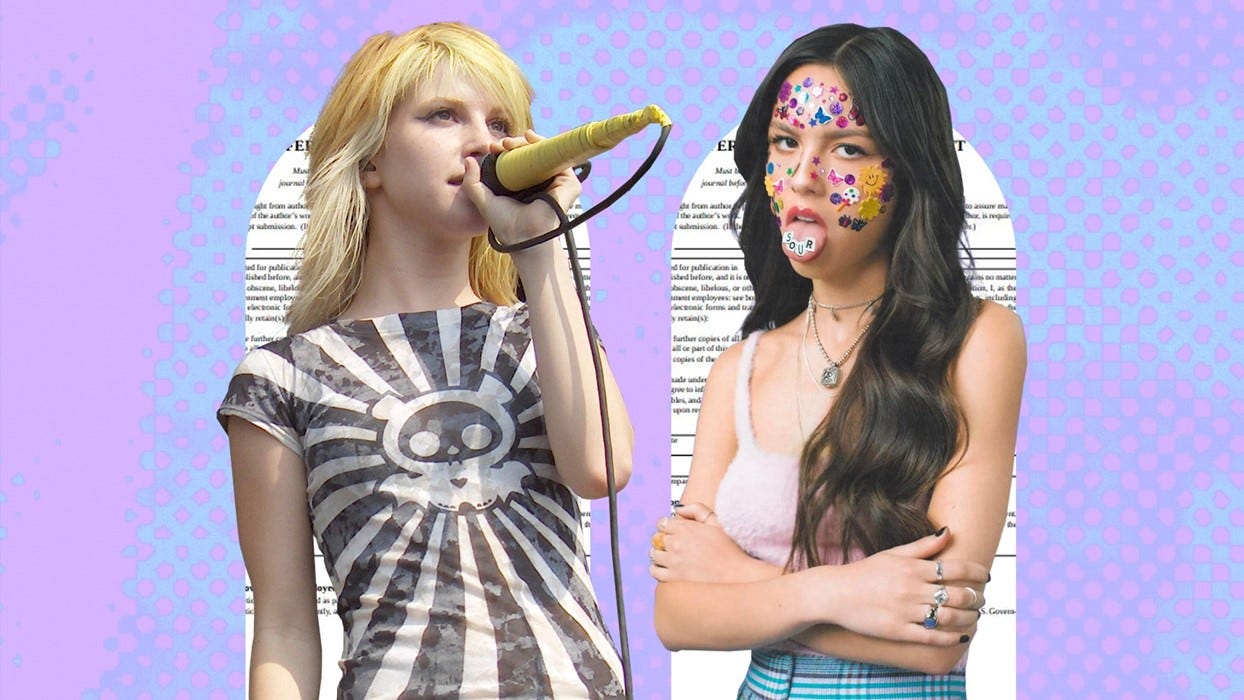

In 2021, musician Olivia Rodrigo retroactively added Hayley Williams and Josh Farro of Paramore as co-writers on good 4 u after videos went viral noting the song's similarity to Paramore’s Misery Business. In interviews before the controversy, Rodrigo had specifically mentioned being inspired by female musicians like Hayley Williams, suggesting that the similarities between the two tracks were no coincidence. The situation was resolved amicably when Olivia ceded than 50% of the songwriting royalties to the duo.

By contrast, Ed Sheeran defended himself against a 2023 lawsuit alleging that his hit song, Shape of You, copied Oh Why, a relatively unknown song by Sami Chokri and Ross O’Donoghue. Ed Sheeran pushed back stating that he had never heard it before and argued that many pop melodies happen to be similar.

The difference in outcome between these two cases is largely subjective. U.S. law states that “the primary purpose of copyright law is to foster the creation and dissemination of intellectual works,”1 but the law provides no method to quantify similarity between two pieces of music, so we look to the context of the writer. In Olivia’s case, she had presumably heard the Paramore song and it felt plausible that she had copied from it (intentionally or subconsciously). Sheeran, on the other hand, made a strong case that any similarities were completely coincidental.

The point here is that copyright law is often applied subjectively toward that goal of "fostering creative works." It must be enforced rigorously enough prevent works from being copied without being so rigid that every Joe Shmo with a similar-ish work can sue. This usually ends up being a judgement call.

Algorithms capable of generating media have further complicated the enforcement of copyright. In March 2020, programmer-musicians Damien Riehl and Noah Rubin wrote an algorithm to generate every possible 12-note melody. They then saved melodies to a hard drive which they physically mailed to the Copyright Office. Riehl and Rubin ended up releasing their melodies to the public domain under a Creative Commons Zero license, but what if they had tried to monetize them instead?

The U.S. Copyright Office clarifies that works “produced by a machine… randomly or automatically without any creative input or intervention from a human author” are not protectable, so Riehl and Rubin’s work is unlikely to stand up in court. But their project reveals a flaw in the system.2 It’s amusing to know that the U.S. Copyright office has had the melody for Sabrina Carpenter’s hit song Espresso since 2020.

The Library of Babel is another interesting case - it contains every book that will ever be written, yet its creators don't go around suing bestselling authors. Juries have a gut sense that copyright is designed to protect work that has been labored over.

We understand that a person should be able to create and own a piece of media even if an unsupervised algorithm has previously generated the same thing. But what about the inverse? What if an algorithm listens to everything and then creates variations that are just different enough to evade an infringement claim? Many feel that this violates the spirit of copyright law, if not the letter.

Part 3: Which future will we choose?

There is plenty of disagreement about whether media generated by AI models will ever be as compelling as work created by the most talented humans. But let's assume that in some markets, fully AI-generated media will someday compete with human creators. Friends I speak to about this possibility tend to hold one of the following beliefs:

Art is sacred. AI should never be more than a tool, and we need to ensure that creatives aren’t replaced.

Some art is sacred. I don’t care if AI mass-produces the background music in pharmaceutical commercials, but I’ll be pissed if Netflix starts recommending AI generated content.

Capitalism baby! The consumer ultimately makes the choice. If an LLM can spit out a best-selling novel, I’ll happily read it.

I can appreciate each of these perspectives, but none deeply consider second-order effects.

Let’s say an LLM (like ChatGPT) ingests every high school geometry textbook ever written and can then generates a custom geometry textbook for every 9th grade math classroom in the unique. It might incorporate the names of students in the classroom, or challenge students to calculate the height of their school's flag pole based on the actual shadow it casts at 3 pm on a sunny day in Cincinnati. Pretty neat!

The key question is: Should the authors of the old geometry textbooks be compensated for the use of their work in training the machine that creates the new ones?

You might say "It depends… How were these textbooks included? Were they in the post-training dataset or just pre-training? Were they included in the prompt? How similar are the custom textbooks to the ones in the dataset?"

Whatever the answers, the result will be the same. If human geometry textbook authors are not compensated for use of their work in training models, and they are out-competed by the custom textbook delivered by the LLM, then they will cease to write textbooks. Maybe that’s ok? Maybe it’s best if all the textbook writing is left to AIs? But we have to be clear-eyed about the direction we’re headed.

Remember, the same copyright laws that apply to textbooks apply to albums, movies, and novels. The same laws that protect your favorite artist also apply to the songs in the “Piano Music for Studying” playlists on Spotify. We can’t differentiate between the media that feels sacred and that which feels simply functional. Whether it's a stock photo or a piece in the MOMA, the law does not yet require AI companies to negotiate with human creators to train models on their copyright protected data, and in some markets, fully autonomous models will soon out-compete the creators that enabled them (even if those creators try to leverage AI tools). In those markets, humans will cease to create.3

When Napoleon's armies spread French copyright law across Italy, they sparked a renaissance in opera composition that showed us something fundamental: creative ecosystems thrive when creators can build sustainable careers. They also showed that the right kind of protection can create virtuous cycles in which creators, distributors, and audiences all benefit.

As we enter the age of AI, we must adapt. This means developing new frameworks for compensating creators whose works train AI models, and establishing clearer guidelines for what constitutes AI-assisted versus AI-generated content. Just as French copyright law transformed Italian opera, our decisions about AI and copyright will shape creative industries for generations to come. Let's make good ones.

P.S. Here are some other people advocating for compensation to copyright holders:

"To be clear, I’m a supporter of generative AI. It will have many benefits — that’s why I’ve worked on it for 13 years. But I can only support generative AI that doesn’t exploit creators by training models — which may replace them — on their work without permission." - Ed Newton-Rex, Former VP of Audio at stability.ai

"It is only fair that you compensate us for using our writings, without which AI would be banal and extremely limited." - Authors Guild Open Letter to GenAI Leaders

“When those who develop such [AI services] steal copyrighted sound recordings, the [AI services’] synthetic musical outputs could saturate the market with machine-generated content that will directly compete with, cheapen, and ultimately drown out the genuine sound recordings on which the [AI services were] built.” - Recording Industry Association of America

"We believe AI can have a constructive benefit for society as a whole, but it needs to account for certain things, and so we’ve always looked for transparency in trading data. We believe creators and IP owners have the right to decide whether their material is trained on." - Craig Peters, CEO of Getty Images

In his 2021 TedX talk, Riehl concludes that “the copyright system is broken, and it needs updating.”

I feel this way about production music - a market in which I used to participate